Part 4 - Modeling simultaneously in UML, Java, and User Perspectives

One of the benefits claimed for the Naked Objects approach is that it helps in the capture and modeling of business requirements.

One of the benefits claimed for the Naked Objects approach (see article 1) is that it helps in the capture and modeling of business requirements.

There is a widespread misconception that modeling implies the use of UML diagrams: it does not. At the Department of Social and Family Affairs (DSFA) in Ireland, whose new Child Benefit Administration system is the largest implementation of a naked object system to date, not a single diagram (UML or otherwise) was drawn during the initial business object modeling phase - yet it is one of the purest examples of business object modeling for a medium-large scale business system in existence.

Instead, the business object model was captured in two forms. One was a textual document defining the high level business responsibilities that each business object class fulfilled (in the manner advocated by Rebecca Wirfs-Brock) - something that is very hard to capture in a diagram. You can view a version of this document on: http://www.nakedobjects.org/section9.html

The other form was the Naked Objects prototype, which allowed business stakeholders to use the objects to simulate real business tasks, right from the beginning of the modeling activity.

We are not opposed to UML: there are certain things that a UML class diagram can render much clearer than the forms described above. Inheritance is one example: the DSFA application used inheritance within the business model, but not to a great extent. UML is also very strong at showing the cardinality of associations; but the vast majority of associations are either '1' or 'n' at either end, and these forms are rendered explicit to the user in a Naked Objects prototype.

Or take the interaction diagrams: why spend the time drawing interaction diagrams, when you can immediately prototype the interaction between the objects and trace it through from the user's perspective? For all the advantages of UML diagrams, we have found they often just delay the realisation of the object model in any executable form. Yes, there are many tools that can generate code stubs from UML diagrams, and vice versa. But even with such tools the process is still long winded, and keeping the two representations synchronised is both labour-intensive and leaky. In our experience, diagrams that are inconsistent with the code are worse than no diagrams at all.

However, our view on this changed when Dan Haywood joined the Naked Objects development community and introduced us to the Together range of development tools (now marketed by Borland).

We should stress that Naked Objects is not tied to any particular IDE; we tend to use Eclipse and we hope eventually to produce a specific Naked Objects plug-in for that tool. But what Dan demonstrated was that for those who do want to be able to use UML representations of a model, the combination of Together and Naked Objects could open up a whole new style of modeling. We'll start with a brief look at how the Together tools work, and then at the synergies to be gained by using them in conjunction with Naked Objects.

At first glance, Together looks remarkably similar to a range of UML modeling tools - such as Rational Rose, Select OMT, and Embarcadero Describe - but the resemblance is superficial. Those competing tools are fundamentally analysis tools: the analyst builds a model in the form of UML diagrams. When the model is ready to progress towards a detailed design, such tools can typically generate code stubs for the model in a particular language. This sounds helpful, but the problem with it is that one now has two representations of the system: the model, and the code. Any elaboration or change to the code may potentially require an update to the model ... or it may not. Most of these modeling tools do allow reverse engineering from code back into a model, with merge facilities, which in theory permits so-called 'round-trip engineering'. But all this places a considerable burden on the development process, with a corresponding impact on overall agility.

Together does not have to worry about keeping the model and code representations in synch, because in its case the model is the code. Actually, it's the other way around: the source code is parsed and rendered either as a UML class diagram, or in a formatted textual form. LiveSource (the name of the underlying technology) is a code parsing engine.

The "Together" name originates because the code and the UML representation are always synchronized together. If the developer edits the UML, then the code changes immediately. If one changes the code (even outside of Together), then the class diagram is updated automatically. Together does support the other 8 UML diagrams, and where possible tries to keep these in sync. If creating a state diagram, or an object instance in an interaction diagram, then one can specify the class for example. In interaction diagrams too, Together will indicate if a method call no longer exists, and will also show if the implementation of that method is at variance with the code.

Dan became an early enthusiast for Together, believing that it could make a significant difference to the software development process in general. In 2001 he co-authored, with Andy Carmichael, a book called "Better Software Faster", that explained how the tool could be adapted on a large or small scale to support particular development processes.

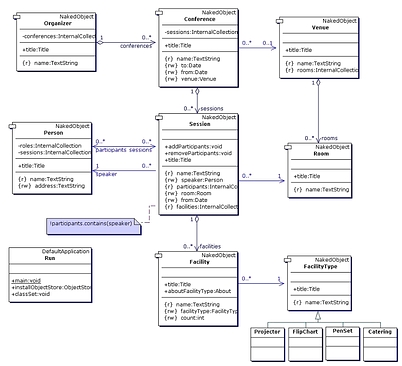

In April 2002 Richard and Robert presented a tutorial session on Naked Objects at OT2002, the annual conference of the British Computer Society OO specialist group (BCS OOPS). As an attendee of that session, Dan was struck by the capabilities of Naked Objects in its own right, but he also immediately saw the potential synergy. Together allows the developer to switch instantaneously between UML and code representations of the object model; combining this with Naked Objects would allow an instantaneous switch to a user representation of the object model. During the course of that first afternoon at OT2002, Dan got the two technologies working together. The two screenshots below show a UML diagram and a Naked Objects user representation of a prototype Conference Management system produced that same afternoon in just a couple of hours, by a group of Java programmers that had never previously used Naked Objects.

These two screenshots show a simple prototype of a conference management system created in one afternoon by a group of Java developers at OT2002. The upper diagram shows a UML diagram, captured using the Together Control Centre, which renders the model simultaneously into Java code and diagrammatic forms. The lower diagram shows a screenshot from the Naked Objects rendition of the same model - created without any additional coding.

Dan has since written a number of customisations for Together, implemented as design patterns. In the context of Together, 'design patterns' are effectively wizards for generating well-defined snippets of code. Shipped with Together are most of the GoF patterns, for example. Dan has developed Together patterns to create a naked object class, add an attribute, add an action, and to add a relationship of specified cardinality and directionality. It is not necessary to have these design patterns to use Naked Objects with Together, but they dramatically improve the development productivity. (You can download the patterns from http://www.haywood-associates.co.uk ).

The net effect is that as fast as you can draw a diagram representing classes, attributes and relationships, you can prototype a system where a user can create instances of those classes (or find previously created instances) , edit the attributes and form allowable associations by dragging and dropping the icons representing the objects. The prototype can then be extended with methods to add richer business behaviour.

Richard and Dan have run a series of events presenting this combination of technologies, hosted by various groups within the British Computer Society, and at the Institute of Electrical Engineers (IEE). Each event typically starts with a 20 minute presentation of the ideas behind Naked Objects. We then invite the audience to suggest an application for which they would like to build a system - real or imaginary. We try to get an application domain that most people could make some contribution to, and, if possible, one that we haven't tackled before (so we don't lose interest, either!). Recent examples include a system for a video rental store, an auto insurance quotation system and, inexplicably, a client management system for an assassination company!

With the domain selected, Richard then asks the audience to identify the most obvious objects within the domain. Part of our methodology is to go straight for the objects - we never start by writing use-cases, although in a proper development project we do write use-cases later on in the process, in order to test the completeness of the model. (There is a lot of evidence that writing use-cases at the outset encourages the separation of data entities and procedures, and thus leads to poor object modeling - see http://www.nakedobjects.org/section6.html for more on this). Dan acts as scribe, capturing the domain objects as a UML diagram using his patterns and Together. Behind the scenes there is Java code but we don't need to show that, so we don't.

We then start to elaborate these domain objects, adding "know-what" behaviours such as attributes and relationships. Typically, within 15 minutes, we are ready to run our first iteration. Using Together to compile and run the code, we start up the naked objects application. Those in the audience who are familiar with UML are always impressed at how it is "brought to life" as naked objects; the less technical members (whose impression is merely that their requirements were somehow being documented) get immediate feedback as to whether those requirements were understood or not. In a 75 minute session, we usually get to perform two or three iterations, which may include new objects, attributes and associations. We also try to add one or two richer methods on the objects. These must be expressed directly into Java code, but because the Java is concerned only with business logic, rather than with input/output, it is remarkably quick to write.

No one would pretend that we had developed a real system in 75 minutes. In real cases we have spent between one and six weeks doing this kind of exploratory prototyping. But one of our house rules is that we never spend more than two hours at a time (preferably only one hour) discussing any kind of requirement without capturing it into executable form on the Naked Objects prototype and then using that prototype to simulate a real business scenario.

Conclusion: Ending the trade-off between Prototyping and Modeling

Traditionally, developers have had to choose between two distinct approaches: rapid prototyping and up-front abstract modeling. Rapid prototyping engages the users and gets the benefit of early feedback, but often at the expense of long term flexibility - the design of the system is driven from the prototyped screens, which are usually driven by very specific and immediate needs, not from an abstract representation of the business domain.

Up-front modeling (also known as 'domain-driven') approaches can deliver much more flexible and adaptable solutions, but it can be difficult to sustain the engagement of users or business stakeholders in such an abstract exercise.

Naked Objects ends this trade-off, allowing developers to gain the advantages of both approaches for the effort of one. Naked Objects facilitates rapid prototyping. But what you are prototyping is not a user presentation, but rather the underlying object model - the user presentation comes for free.